The Big Money

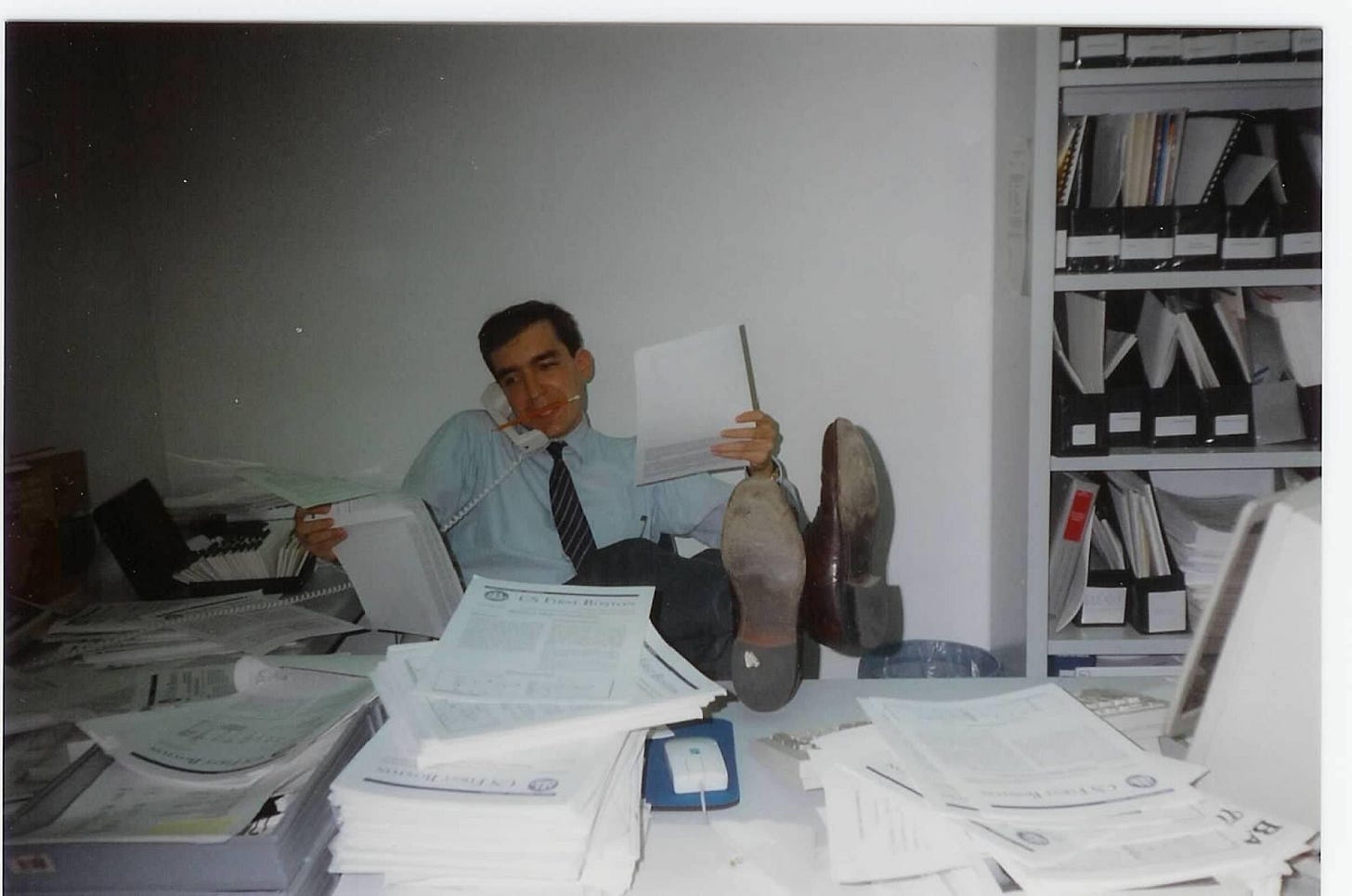

Portrait of the analyst as a young man

Mrs. Jakab and I have turned into curmudgeons who bore our three adult sons with tales of walking barefooted five miles to school in the snow uphill both ways. One recurring theme is how tough it was to get a good job in the recessionary early 1990s.

Young people laser printing cover letters and résumés and mailing them by the dozen must have been a major profit center for Hewlett-Packard, Kinko’s, and the postal service. The vast majority of those shots in the dark didn’t even get a polite “don’t call us, we’ll call you.”

But at least we had one advantage then: The world was a less-efficient place. There was no LinkedIn or even internet where you could screen thousands of candidates for a job. If you showed up in the right place at the right time and made a good impression on someone who needed to hire a person quickly then they might just do it on the spot.

Young people who ask me these days how I got into investment banking might enjoy the colorful story, but I’m afraid they aren’t going to glean any useful career advice.

There’s a well-worn career path now: Get into a target college (there are about 12 to 15 of them) by being an amazing student or a good enough student and good enough athlete (lots of Lacrosse players on trading desks). If your family’s name is on a building at one of those colleges, or your dad plays golf with a guy on the board of trustees, then that’ll work too, but then you probably can already get a job at Morgan Stanley with your old man’s help.

Then hit it off with the recruiter when he or she comes to your college. That’s the last step to joining a class at a big firm as an analyst (meaning “analyst” the rank below associate, VP, director, etc, not necessarily the job description, which is confusing) and work crazy hours doing Excel spreadsheets and PowerPoint presentations.

These days that’s often a stepping stone to a potentially better-paying job in private equity. In the 1990s it wasn’t really an option: No matter how brilliant and hard-working you were, after a couple of years it was off to an M.B.A. program so you could come back and start climbing from the next rung at a similar bank.

If all went well, in 30 years you’d be a filthy-rich managing director with a house in the Hamptons, a ton of frequent-flier points and kids who barely recognize you.

That wasn’t my path. In late 1991 I met a fellow student at Columbia, still a good friend, who had been an investment banker before enrolling in the graduate program we were both starting. I had no idea what an investment bank was so I asked him. I tuned out his complaints about 100 hour weeks and abuse by his bosses and fixated on his salary: $80,000. Plus bonus.

It sounds silly, but it was an unbelievable amount of money to me then. I asked how to get a job like that. He said “hey, you’re bilingual, and they’re going to need people who know finance when they privatize everything in Eastern Europe. Just take every finance and accounting class you can at Columbia Business School.” So I did (you were allowed to do that then—six classes a semester instead of four) and got internships that would at least let me find out who might hire a clueless young person like me.

The next step was to turn my mostly useless theoretical knowledge into a job in finance. With the names and postal addresses of a bunch of local finance guys in hand (remember, no internet yet—this took some work), I bought what’s called a courier ticket to Budapest. Before UPS and FedEx were truly global, people would sometimes send packages abroad as someone’s luggage by buying the cheapest airfare.

Then they had to find someone who really wanted to fly to that place cheaply. So for hardly anything I took the subway to a warehouse in Queens, got driven to JFK in a truck and brought a box that I really hope didn’t contain drugs to a stranger in Helsinki. Then I caught a connecting flight to Budapest wearing my interview suit (since I couldn’t check a bag).

Unlike the spray and pray method of sending out letters to HR departments, nearly everyone said they’d meet me in person over the few days I told them I’d just happen to be in Budapest. All but one made me a job offer, so I picked the role that sounded best, “senior associate” in corporate finance at Coopers & Lybrand (now PwC).

My job was mostly being a glorified auditor and I was bored stiff. At least I learned some accounting. I also met a trader at CS First Boston whose girlfriend was my manager. They needed a research analyst ASAP and she saw that it’d be a better fit, so I hopped in a taxi and interviewed there as soon as I heard about it. Two days later I was meeting the head of research in London along with a Coopers colleague, now one of my best friends.

The head of research, Dan Meade, bless him, made a spur-of-the-moment decision to just hire us both. The whole thing was comical. Neither of us had any idea that investment banks spent money like water. Yes, they had flown us both to London business class, but we didn’t want to abuse their hospitality.

Since we had hardly any money and the whole interview process had taken a long time, we weren’t going to make the evening flight back to Budapest. The boss’s secretary offered to call us a cab that we wouldn’t have been able to afford (of course they probably would have paid), so we just said we preferred taking the Tube. She gave us a very odd look.

We went to Victoria Station with no clothing or even toothbrushes—only our briefcases and about £50 between us. We walked over to the Thomas Cook counter where they arranged cheap lodgings. Knowing how much it would cost to take the Tube to Heathrow the following morning, we rented a room in a fleabag near Paddington Station for £30—”The Hotel Imperial,” I believe it was called 😂—and slept in the same sagging bed. I still remember the woman at the Thomas Cook counter:

“They wanted to charge £35, but it’s not worth that much.”

Showing some early analytical chops, we calculated the optimal money-to-calories ratio and bought ourselves each a McDonald’s Happy Meal. The optimal money-to-culture ratio at the moment was zero so the next morning we visited the British Museum, which was free (then at least), and we had a nice, educational morning before our return flight.

We’d soon learn why we were hired so quickly. The bank had won a mandate for the IPO of Hungary’s most successful private company and they needed a bilingual analyst to write a report and market it to clients. I was able to start two weeks earlier than my friend so that deal fell to me.

It still wasn’t fast enough. The bank assigned a middle-aged analyst who covered mining stocks to train us, but the deal couldn’t wait so she wrote the initiation report with my name also on it before my notice period was over. It would be my job to take over her model and baffle clients with my bullshit.

As I said, I knew hardly anything, but hardly doesn’t mean zero. I’m telling this to you, dear reader, in the belief that there’s a statute of limitations on financial malpractice. The mining analyst might have known less about finance than me at that point, which is saying something.

After perusing her model and not being able to arrive at anything like the value she got, I discovered that, while the deal size had changed (30% fewer dollars raised), her spreadsheet hadn’t. So the number of shares was correct, but not the cash. Oops.

Then I went to the company to chat with its chief financial officer. It seems one of their most-lucrative businesses, being the dominant seller of cellphone service in Hungary at the time, wasn’t going so great.

I called her right away but, instead of fixing the problem, and also letting clients know that the business was doing poorly, she shouted and warned me of the consequences of changing “my” buy recommendation, how it would end my career, etc.

What would you have done? Well she was my boss, sort of. I fixed the numbers, fudged a few things, and put out one more report with a “buy” recommendation before downgrading the stock to “hold” as soon as it seemed acceptable. I also had a strong suspicion the CEO was a crook (he was). But hey, it could be worse, right?

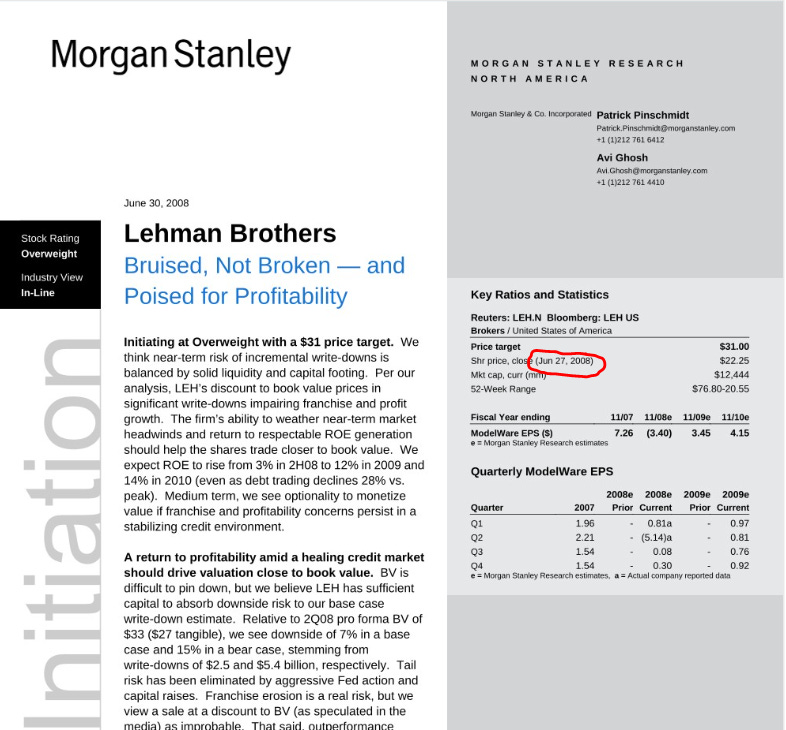

It was an inauspicious start to my career in equity research, but I tried to make up for it by being stubbornly ethical after that. I downgraded the hottest stock on the market near the end of a massive boom years later and was basically cut off by the company’s management, which held a conference call with investors and analysts except me (the stock fell 85%).

I’m not making myself out to be a hero. The sort of analyst I was, covering emerging markets where trading was lucrative but deals were intermittent, meant you were rewarded for being useful to investors more than bankers.

I was good at that. In less than five years I was heading our whole team and within six I was a managing director.

It had nothing to do with my decision to become a journalist, but being an equity analyst isn’t what it used to be. The way banks reward employees and the way information is distributed, especially in the U.S., makes it much less lucrative and less-central to the whole operation.

After 22 years as a journalist I still make a fraction of what I did, not even adjusted for inflation, as in my last few years as an analyst. Now I might make more than some analysts. If money is all you’re after, pick a different role at a bank.

Back then I felt really important because my opinions could sometimes move stocks. These days that’s rare. If I had to start in the profession now I’d try doing the same thing anonymously inside a hedge fund—it pays better and is more about the analysis rather than the marketing.